Unlike most Americans, I was alone on July 4th and decided to “celebrate” by catching up on my netflix queue. One of the films I watched was Atlas Shrugged (part 1). I’d already heard the production was sub-par, so that wasn’t surprising. What I was surprised with was how unambiguous but also uninformed the economic talking points were. If you don’t want spoilers about the book or film, stop reading now.

It seems not a single character with a name in the film has less than a million dollars in the bank. Some of them are clearly defined as “bad” and others “good,” but the misery of the 1% is a hard concept to sell. Although I hated Somewhere (it’s unnecessarily boring, but maybe that’s the point), it at least paints a more “human” portrayal of the ennui of access to a bottomless bank account. In Somewhere, rich people have character flaws that don’t involve greed, and expensive cars can break down. In Atlas Shrugged, we owe the rich more than money, as the world would grind to a halt without their tireless commitment to keeping us, the talentless (or else we’d be rich, right?) masses afloat. There are numerous NOT subtle hints at this message.

On the way to work a character in a limo drives past a “welfare distribution” truck from the government. The welfare line curves around the block. I imagine the filmmakers wanted us to identify with the sleek black limo and recoil in disgust at the losers waiting for a free meal. As the character got out of the limo and walked into her giant office building with intricate marble walls and floors, I couldn’t help but think about how much of her accumulated wealth could have bought loaves of bread for those people. In a later scene, IN A LIMO no less, we hear in the background that gasoline has hit a record high price. At the beginning of the film a man already stated “If times is tough for the rich folk, do you have any idea how hard it is for us (the poor)?” Yes, we’re expected to identify with the people in the limos in this film, because if they JUST didn’t have regulations to deal with … um… they wouldn’t be as stressed out all the time?

Even a day after watching the film I’m still not sure who I was supposed to identify with. I think, given the time spent showing their “strong moral fiber” we’re supposed to identify with Dagny Taggart, a railroad heiress and Mr. Reardon, a steel foundry owner. However, in act three the married Mr. Reardon sleeps with Dagny. Isn’t that bad? Oh, that’s right, act one established his wife is a bitch that doesn’t work and doesn’t appreciate how cool the steel business is – so it’s okay to cheat on her.

Although the protagonists were confusing, the points the film was trying to convey about economics and government were anything but. In fact, the “morals” of the story were stated in plain language spoken bits that likely frustrated the actors involved. In one scene Mr. Reardon bluntly explains to Dagny that a “Revolutionary” new energy company failed because (paraphrasing as I couldn’t find the script online to qoute directly from) “The owners decided to flatten all wages to the same amount regardless of talent or skill level and the good people left, the remaining employees couldn’t handle the workload and the company folded.” This falls in line with the central theme through the entire movie of the government encouraging policies that right wingers today would like you to believe are akin to our “Socialist president”, but are actually more akin to hardline Marxism. Repeatedly the film brings in characters from the government only to show how currupt they are. In the world of Atlas a new government rule on monopolies outlaws any one individual from owning more than one company.

Considering Roosevelt actually DID break up a railroad company and it neither doomed America nor the railroad industry this is especially telling of the filmmakers’ disconnect from reality. In the film we literally see scenes of Mr. Reardon’s other companies being taken away from him, one by one. Apparently he owned all the underlying suppliers for his own business. It is never explained to the audience that this isn’t really what a monopoly is or why they are usually broken up. Although owning the supply chain can certainly help you build a monopoly in a market, it isn’t a de facto proof of a monopoly as is presented in the film. In the film we are led to believe that Reardon is competing with other manufacturers who, presumably, have their own supply chains. In fact, since Reardon is using a brand new and different type of steel, we can only assume that he actually isn’t using monopolistic practices at all as we know them in the real world. In this case, the prosecution of Reardon is done to make the persecution of monopolies look bad, but my mind was exploding with incredulity as I watched. In a preceding scene the other steel companies and market players literally get together over dinner to sponsor legislation blocking the manufacture of a cheaper type of steel. In the real world, under the same Antitrust Act that governs monopolies, it would be Mr. Reardon’s competitors that would be feeling the heat for price fixing.

It also occurred to me that it was odd that with all the negativity surrounding the “government” in the film, and the heavy handed badmouthing of lobbyists, it was confusing how such rich and powerful men like Reardon couldn’t have a lobbyist of their own, like in real life, and prevent the passage of the new monopolies act.

I’ve digressed, though, let’s get back to that mysterious energy company that went bankrupt. After all, the government didn’t shut them down, they did it to themselves by voluntarily using a “socialist” wage policy, right? The entire sequence was shocking to me how blatantly the filmmakers pretended that large corporations always have the public’s best interest at heart. When a revolutionary energy company gets shut down, what are the odds it was “socialist policies in the workplace” and not a buyout from a threatened competitor? The makers of this film (and anyone that identifies with it) need to sit down in a Clockwork Orange torture chair and watch Who Killed the Electric Car. Hint: it wasn’t socialist wage policies 😉

The film started to verge into Orwellian territory (as any un self-aware right wing “think” piece does) when the Ministry of Science (or whatever it was called in the film) releases a bogus report about the structural “dangers” (they’re never detailed) of Mr. Reardon’s new steel fabrication. It is a given, and admitted to Dagny by a scared government employee, that the report is bogus and the steel is safe. How do we know it’s safe? Dagny, our hero, took engineering classes back in college. Done. Despite the obvious canard that one woman, who is a career manager, not an engineer, can judge the veracity of steel by herself because she has an engineering degree, the larger crime the filmmakers commit is to play the popular right wing anti-science card. We’re lead to believe that “scientists” in Atlas make it up as they go along and CEOs never tell a lie. Sadly, based on polling about global warming alone, we can conclude that this view is not just an allegation for many in the flyover states in real life, but an affirmation of fact. Science is not to be trusted. It’s perhaps a larger problem in the real world than in the movie, which is the scariest thing, as that part of the movie in fictional 2016 most closely parallels the real world of 2012.

The biggest ideological failure in the film is the gross interpretation of the invisible hand. Instead of viewing economics as activity governed by scarcity of resources, the film pretends the world has unlimited resources and if it weren’t for the government (see: Democrats) we’d be living in a utopia. To bring the point home, the answer to the question “who is John Gault” is answered by John himself saying he’s created just such a utopia, where individuals are unencumbered by government to put their ideas in action. He calls it “Atlantis.” Yes, the words are actually said on film. It is perhaps the most hilarious line in the film. To further expand on what Atlantis is and why John is taking away all the “good” inventors/managers/accountants you have to watch part II, of course.

Or you could just go to wikipedia and read about the book. Apparently “Atlantis” is code for John’s super double ultra mega secret gathering of powerful decision makers (Bohemian Grove, anyone?). John has been convincing these frustrated “meaningful” people to go on strike so “helpless” (yes, the non business owners are actually referred to as that in one scene) people can see their value and convince the government to leave them alone. Of course, in real life, the invisible hand would push other competitors into the newly opened market since barriers to entry would be incredibly low. Imagine if Michael Dell, Steve Jobs and Bill Gates all suddenly left the computer industry in 1999. Would the world stop using computers and wait for them to come back? What does your most basic understanding of Adam Smith’s economics tell you? Apparently Ayn Rand didn’t know as much about economics as you do!

It all feels a bit too much like Christian Rock Hard, which essentially tells the same story (while hilariously lambasting the Christian Rock industry simultaneously) but is endlessly more poignant and more enjoyable to watch. However, unlike Atlas, at the end of the Southpark episode the boys realize that their drive to make music wasn’t to make money after all and they start playing again. The point of Atlas Shrugged is that talent without reimbursement should not be used. We see this in the political sphere right now when taxes come up. Republicans can always find some rich man who vows to quit his business if he has to pay 1% more in taxes or pay for healthcare or…whatever the issue is that democrats are doing to give him a “hard time.” This is basically the open admittance of purified greed. Which is weird since most of these people are supposed to be god-fearing Christians… right? Jesus encouraged the rich man to give up everything he owned to the poor, not fight for every penny.

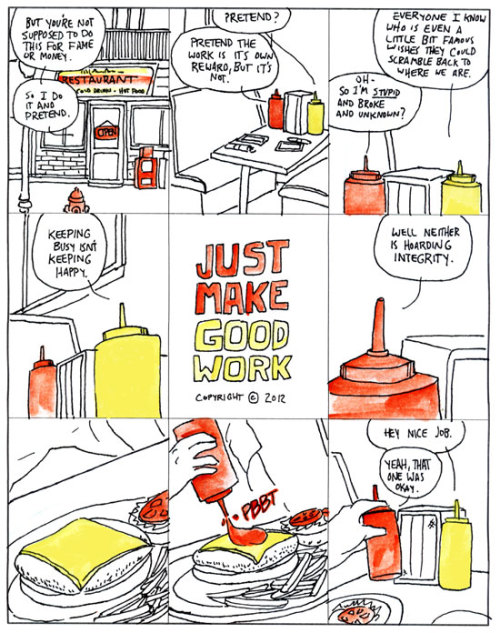

In the last ten years I’ve skipped up a couple of tax brackets. I don’t enjoy paying more taxes every year, but I’m sure as hell not going to quit my job for an easier one so I don’t have to pay more. That (making money) doesn’t even address the core of the argument that I fear many will miss altogether, but the eight year old boys in South Park could see clearly. My definition of an “Artist” is someone that has great skill in and enjoys doing their work. Artists don’t do it for the money; that’s the difference between Art and Avarice. This film proposes just the opposite; that sans money nobody would follow their calling as avarice is a natural human proclivity and creativity is only a means to satisfy it. Can you imagine the loss of art and culture if this attitude was adopted before the renaissance? Art and commerce have always been linked, but if you don’t know which one comes first, you’re not an Artist.

I’ve always been curious about, but never read, Atlas Shrugged. I’m certainly less inclined to read it now.